Back to Workwear event

We hosted a great workshop on Sept. 19 called “Back to Workwear.” Tickets went quickly and we had a full house. I am humbled by how much interest there is in what we do, how we work and why we source specific materials.

We spoke about textiles first and, specifically, what’s so special about Japanese selvage denim.

To kick things off, we looked at the history of this cloth. The first denim cloth was made in the French city of Nîmes and was used to make sails for boats. It was a type of cloth called serge de Nîmes (the term serge refers to the twill or diagonal pattern that can still be seen up close on most pairs of jeans but, over time, the fabric would more commonly be shortened to de Nîmes). It could be more densely woven, and its structure provided some natural give, or elasticity.

During the gold rush to the Klondike, Levi Strauss, a German-American entrepreneur, popularized using denim fabric and dyed the warp yarns with what was, at the time, cheap natural, indigo dye. This is the era when American denim as we still know it today was born. It was during the second World War that Japanese culture was introduced to American denim via U.S. troops. At the time, Toyota (or Toyoda, as it was called then) was a loom manufacturer and it made improvements to the shuttle loom that was used to produce denim. Most notably, the Toyoda machine stopped automatically when its bobbin of yarn ran out.

The shuttle loom is key in selvage denim. It weaves much slower with yarn under much less tension than rapier looms, which are used in a lot of denim production today. I have posted a video below that shows the looms in operation at Kuroki, a denim mill in Japan’s Okayama prefecture, which I visited this past spring. In it, you can see a shuttle with a bobbin of yarn on it travelling back and forth. Its lower tension gives the fabric more elasticity across the body without the need to introduce synthetic Spandex, which stretches out over time and does not return to its original shape. This means a pair of jeans made from selvage denim will shape and mould to your body and come back to its original shape when washed. The other benefit is a beautiful, finished edge of the fabric, which is usually in a different colour and can be used as the finish on inside seams and in some subtle details in the garment. Incorporating a discrete selvage detail on a piece is appreciated by others who share a love for this historic cloth.

A Toyoda shuttle loom in action.

The contemporary rapier loom creates wider fabric under higher tension by passing the yarn back and forth off a spool using a sort of clamp. The yarns are cut each time they are passed through, producing a rough edge with loose threads, and the fabric does not have the same natural give around the body. Most contemporary denim is made this way. My video of a rapier loom in action is below so you can compare.

A contemporary rapier loom in action.

Today, Toyota no longer makes its special Toyoda looms and all the newest machines still in operation are from the late 1940s and 1950s. If a part breaks, a new part needs to be made from scratch. The care and skill that keeps them operating is another detail valued by fans of selvage denim. Despite all of these challenges, many mills in Japan are committed to continuing to produce denim in this way. In Ibara, there are still approximately 25 mills producing selvage denim for a domestic culture that’s still obsessed with vintage Americana.

A rare loom weaving a durable type of cloth that has clean, finished edges and natural elasticity is only half of selvage denim’s appeal. We can’t talk about workwear without also talking about natural indigo.

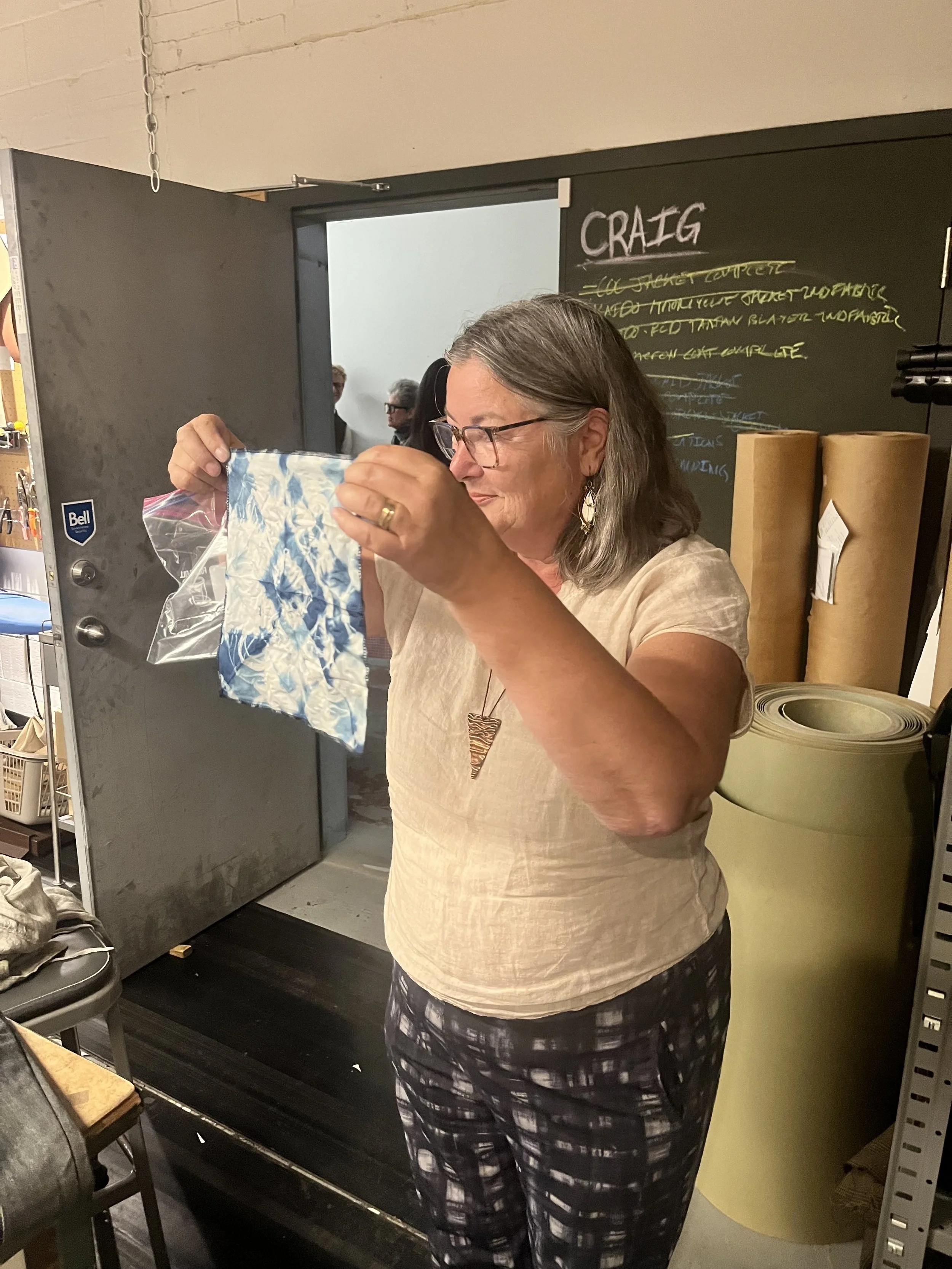

Gitte showing off the pocket square she dyed in indigo during our workshop.

Indigo comes from many types of plants. It is usually extracted from plant leaves by a process of fermentation, where bacteria eat all the plant matter except the indigo. There are many different processes for extracting indigo that have been developed all over the world. And while it was viewed as a cheap dye in the past, indigo production is labour intensive and is by no means affordable by today’s standards.

I have worked with indigo at an artisanal level for over a decade. It works much differently than other dyes. To get a deep blue, I dip into a stew of powdered indigo extract, fructose derived from boiled dates, calcium powder, henna and water and then expose it to oxygen multiple times. Indigo is not soluble in oxygen, which is present in regular water. When Indigo is dissolved in water, it’s actually a yellowy-green copper colour with a blue skin on the surface where it comes in contact with the air. It’s not until you expose a fabric dipped in indigo to oxygen that it starts to turn blue. Our workshop guests had the opportunity to try dipping their own pocket squares into an indigo vat I built and witness this process firsthand.

I was very curious to understand how this multi-step dipping and oxidation process worked at an industrial scale. You can see it in the video below where, at Kuruki, I was invited into the dye house to see their process of rope dying. Here, they are dying the warp yarns that will make up the length of the cloth by drawing them through a first vat of indigo and then raising those yarns 10 metres into the air. The yarns travel up and down this 10-metre span 10 times and then enter a second vat of indigo and continue the same “skying” process. The yarns can be dipped in one continuous process this way through up to 10 indigo vats.

Indigo” rope dying” at Kuroki

According to my host at Kuruki, Mr. Ii, most North Americans prefer a lighter indigo for a more blue jean that is dipped four times and most Japanese and Europeans prefer something darker that is dipped seven times. Dipping 10 times will produce an almost black-blue. Below is a video of yarns dipped four times and yarns dipped seven times to see the difference.

Comparing four indigo dips with seven indigo dips.

Why does natural indigo matter? First, it’s a plant and using it as a dye is not harmful to the environment. The water used in the process can also be recycled as long as the concentration of indigo is monitored and increased as needed.

From the perspective of wearing jeans, what’s special about the stain is that it fades. If you cut a yarn dyed with indigo, the inside of it will still be white. In combination with a natural cream cotton yarn that is woven as the width of the fabric, this causes the denim to streak and fade where you rub on it, fold it and wear it. The cloth becomes more mottled as it patinas and wears. This effect is so desirable that many jean brands achieve it using chemicals, enzymes and sanding so your new jeans look well-worn before even putting them on. We prefer the authenticity of a wearer putting their own unique mark on the piece we make for them.

Where do we as makers of garments come in? Many of the details seen on workwear are related to the industrial sewing equipment that was developed to make it more affordable. Just like the Toyoda looms, a lot of that equipment is no longer produced and contemporary versions can often only handle lighter weight materials and more flimsy thread.

A regular sewing machine creates what’s called a lockstitch that does not have much flexibility under tension. A chain stitch, which is preferred when sewing denim, is created with a series of loops that have a natural give and allow the denim to mould and shape to your body. Below is a video showing the difference in these two types of stitches.

chainstitch vs lockstitch

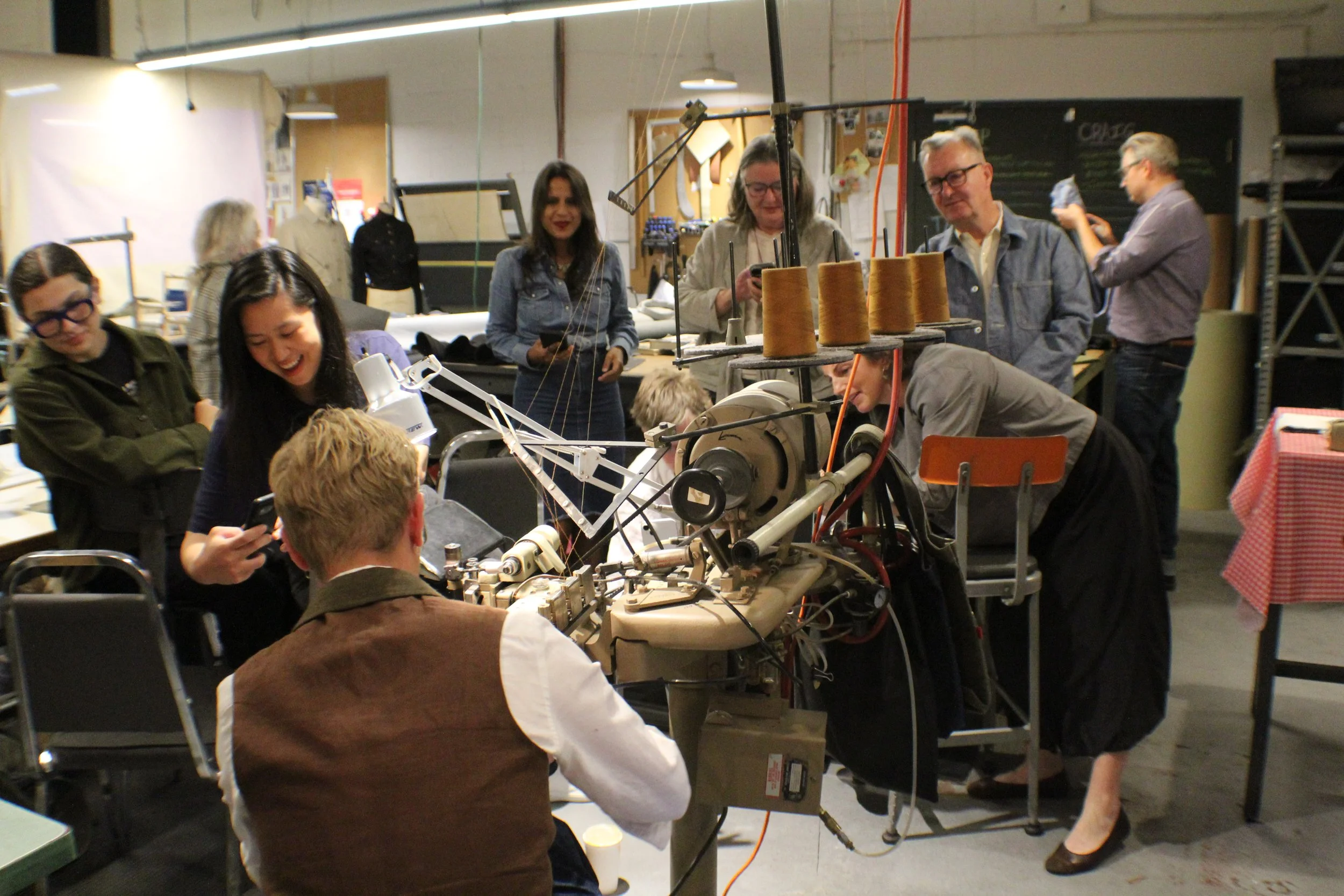

At the shop, we have a Union Special felling machine that Tom demonstrated for our guests. This model folds over the cloth and produces the clean finished seams you often see on the back of a pair of jeans. It sews two or three rows of stitching. It is not easy to use and requires a lot of training as well as adjustments for any change to the type of cloth running through it. It is more aggressive with pullers and folders than can manage the heavier weights of denim we normally work with. This is just one example of specialized denim equipment. We use at least 10 different specialized machines to craft one pair of jeans.

Tom demonstrating our Union Special felling machine

As durable as that pair will be, selvage denim does still wear out. When a piece of well-loved workwear that we’ve created returns to the shop to be mended, new stitches or patches add more character to the piece. Over years and, hopefully decades, the story of your denim slowly builds to become a piece that is entirely, uniquely your own.

A well worn pair of jeans made and mended in our shop

Thank you to everyone who came out to the event. Thank you to Takuma Kobayashi for the translation of emails and phone calls. Thank you to Seiko Kudo for showing up last minute to translate in person. A very special thank you to Mr. Naruhiko Ii for sharing your passion for the production of selvage denim with me, touring me through Kuroki’s faculties, taking me out for an incredible Japanese lunch and for driving and hour to take me back to the train. Thank you to the President of Kuroki Mr. Tatsushi Kuroki for opening up your factories to me.

Philip with Mr. Ii on the Kuroki weaving floor