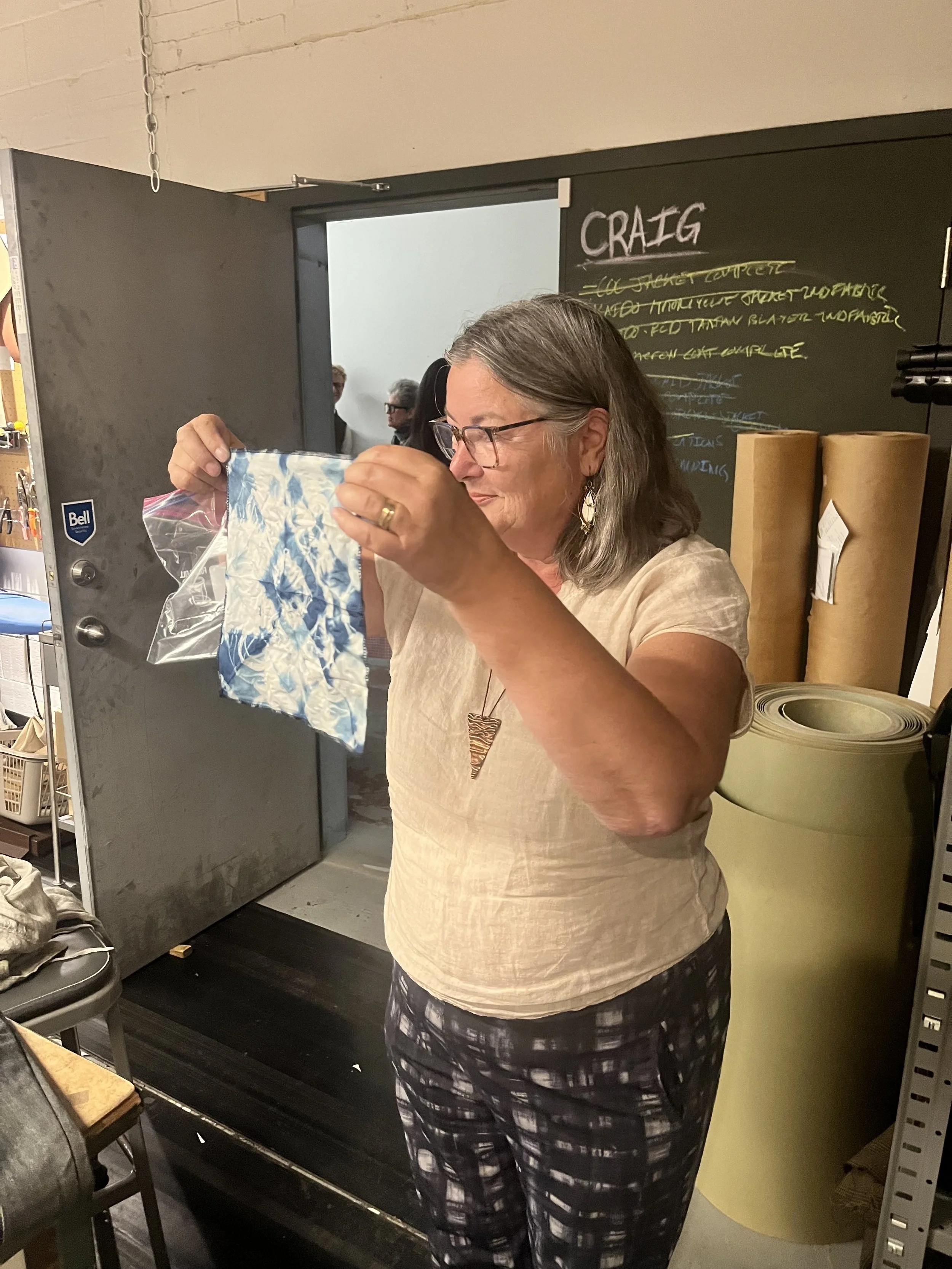

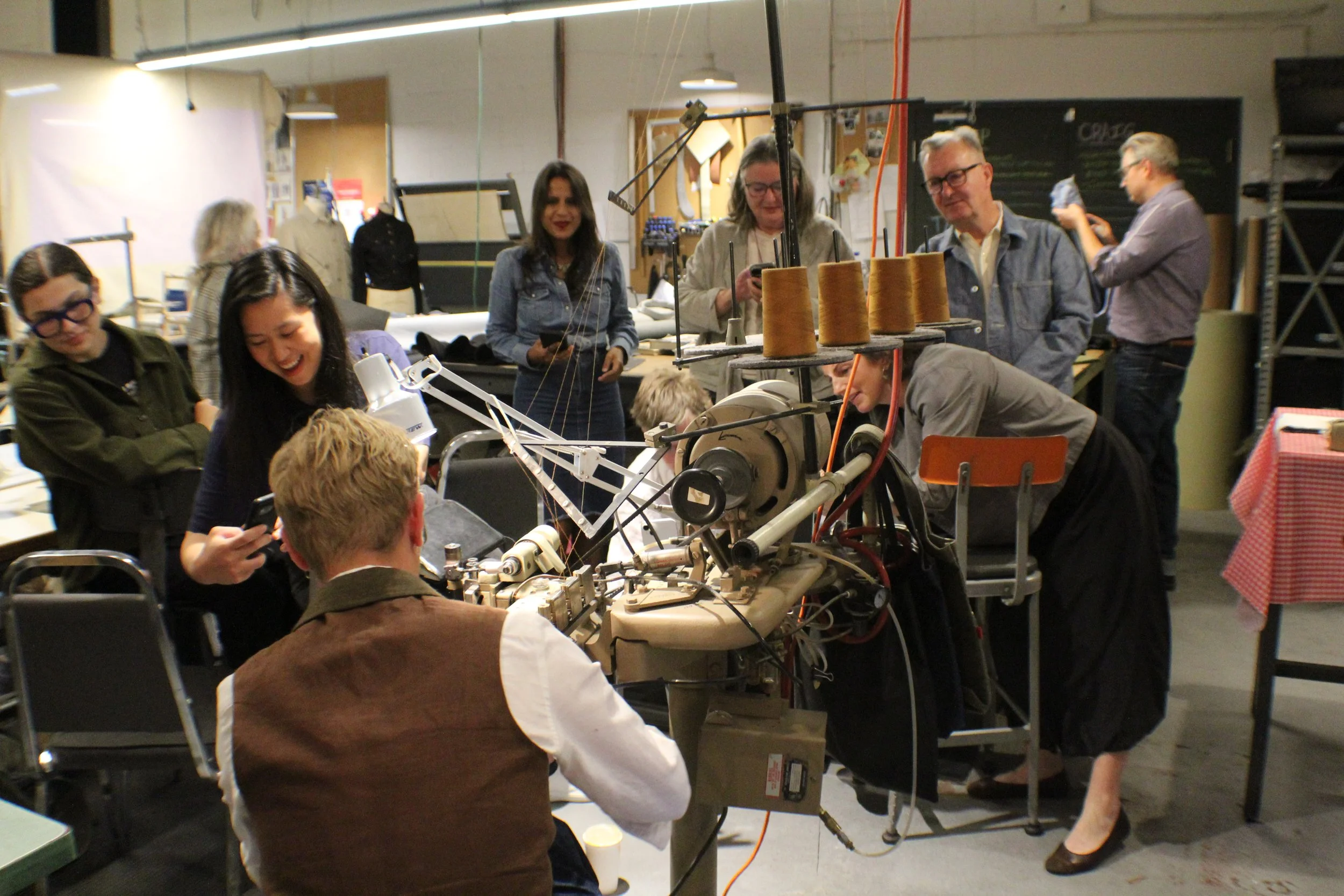

Each month one of our tailors makes their top choice from our newly opened Ruby Room fabric library and proposes a potential theme and design. Here is our Monthly Mood Board December 2025 edition.

December Monthly Mood Board

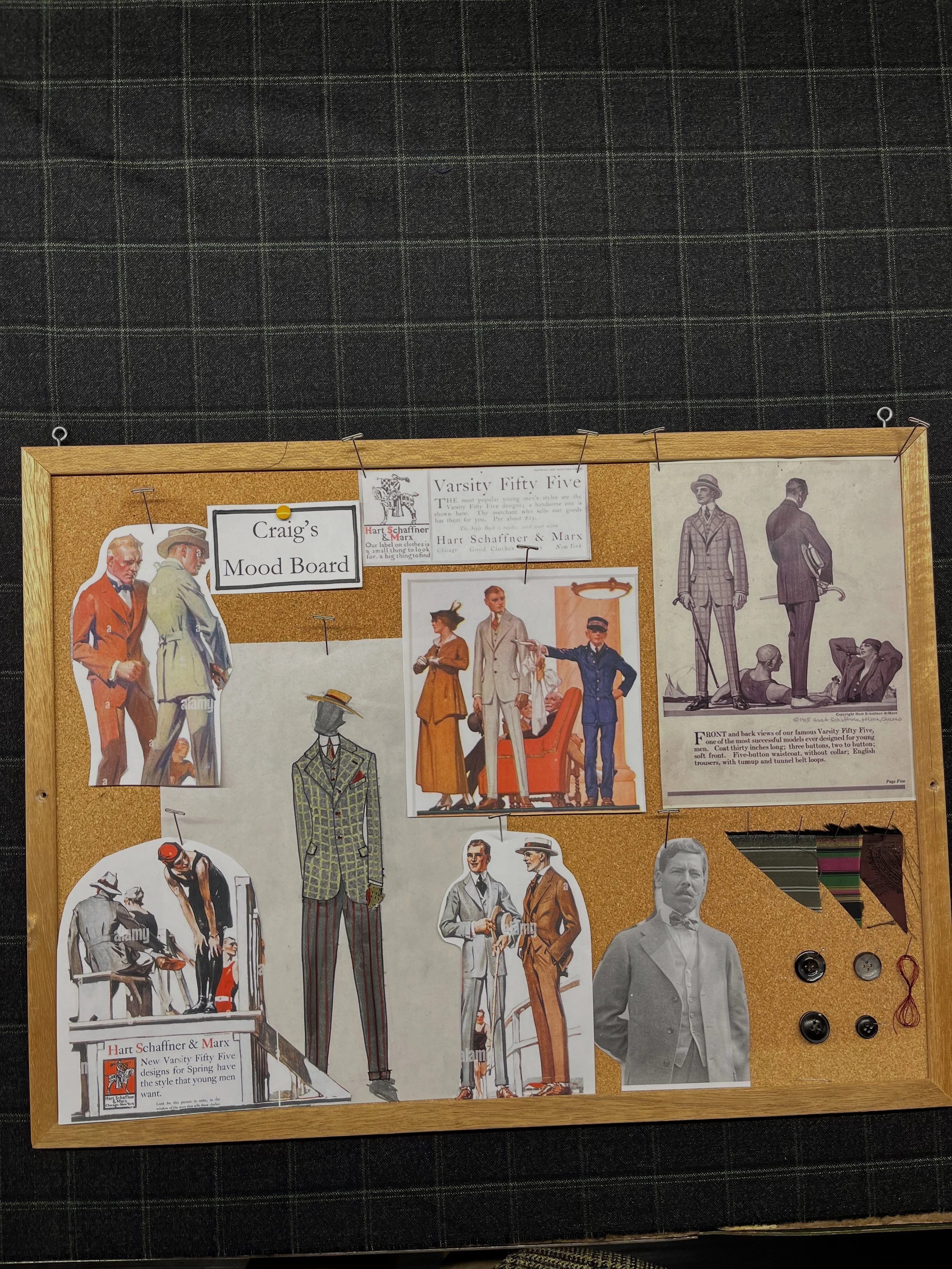

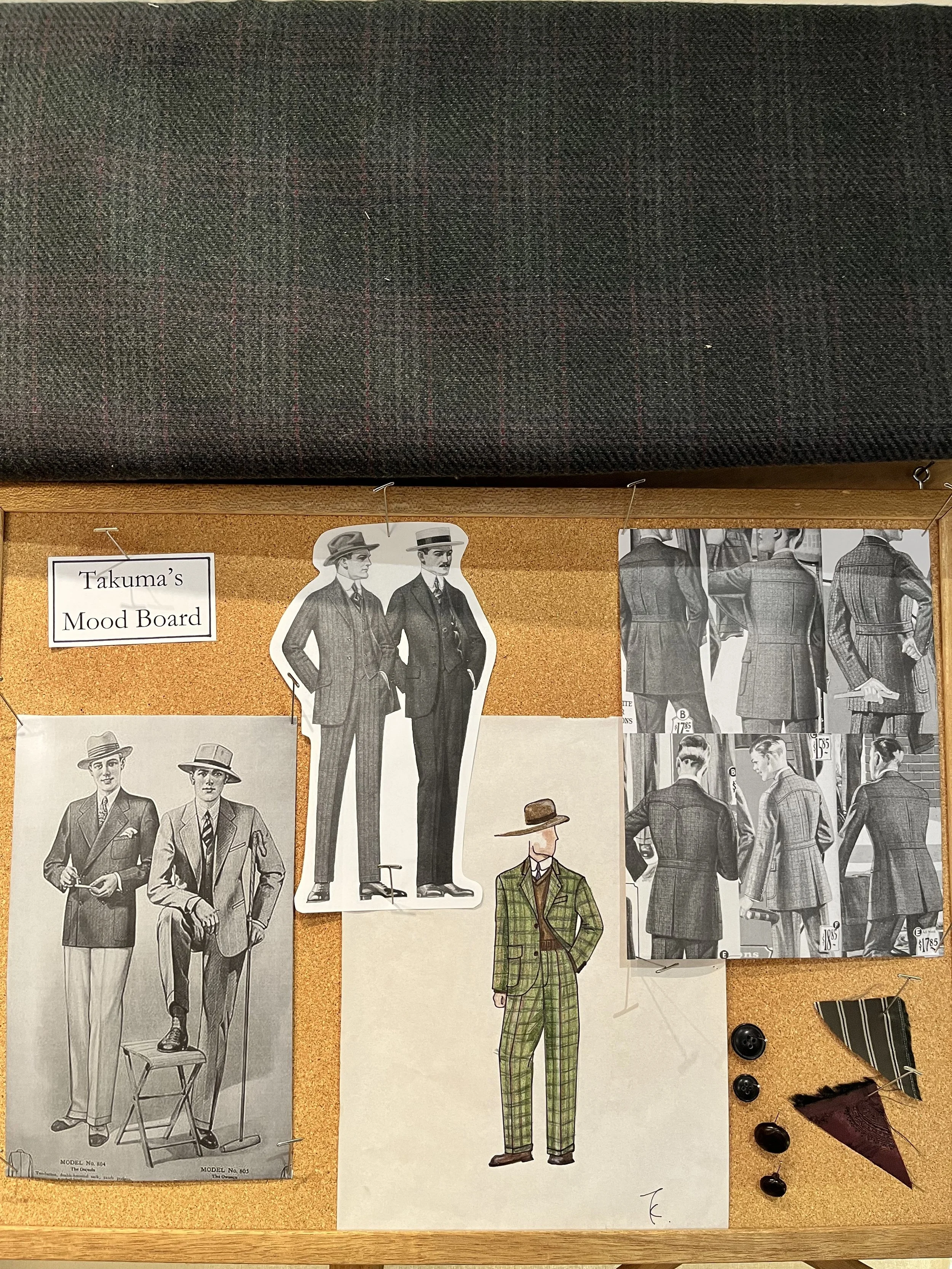

Craig has been looking at and dreaming of a specific 1915 suit reference that was on the inspiration board behind our irons for some time. Now with the Ruby Room open, he’s found the perfect cloth to execute this with. For December Craig chose this lovely heavier flannel windowpane check with grey background and a green stripe, perfect for the holiday season.

1915 suit reference

Craig’s illustration proposes a slim cut three button single breasted sack coat. We generally refer to this specific style of buttoning as a Two in Three or sometimes also called a 2/3 roll. The canvas is cut so the lapel will roll to the middle button but the cut also allows the wearer to do up the top button. This is where the “sometimes, always, never” rule comes into play, you sometimes button the top button, always button the middle button and never button the bottom button. We’re all for breaking rules but it's handy to know the etiquette. In a typical 1910’s style the jacket illustrated has minimal padding, is narrower in the shoulder and cut with a flat crown of the sleeve. The lapel is cut slightly wider with a high gore line and an extra button and hole so the wearer might actually do up the collar up all the way to the neck. The jacket foreparts cut away slightly and flap pockets are cut low to accentuate a narrow waist and long torso. A longer jacket and pegged trousers with a narrow cuff contribute to an elongating of the figure and a sharp look.

Craig’s Illustration

Interested in this look? Book a consultation